Wheat pathology research a practical way to help producers

Mackenzie Hladun is fascinated by the basic principles of how a host can defend itself from disease, whether it comes to animals, humans or plants.

By Nykole King“I’m just so intrigued with how a host can identify a disease and fight it off. I don’t know if it's the resilience factor or if it's the have-to-survive factor in the host, but pathology has always just clicked in my brain,” said Hladun.

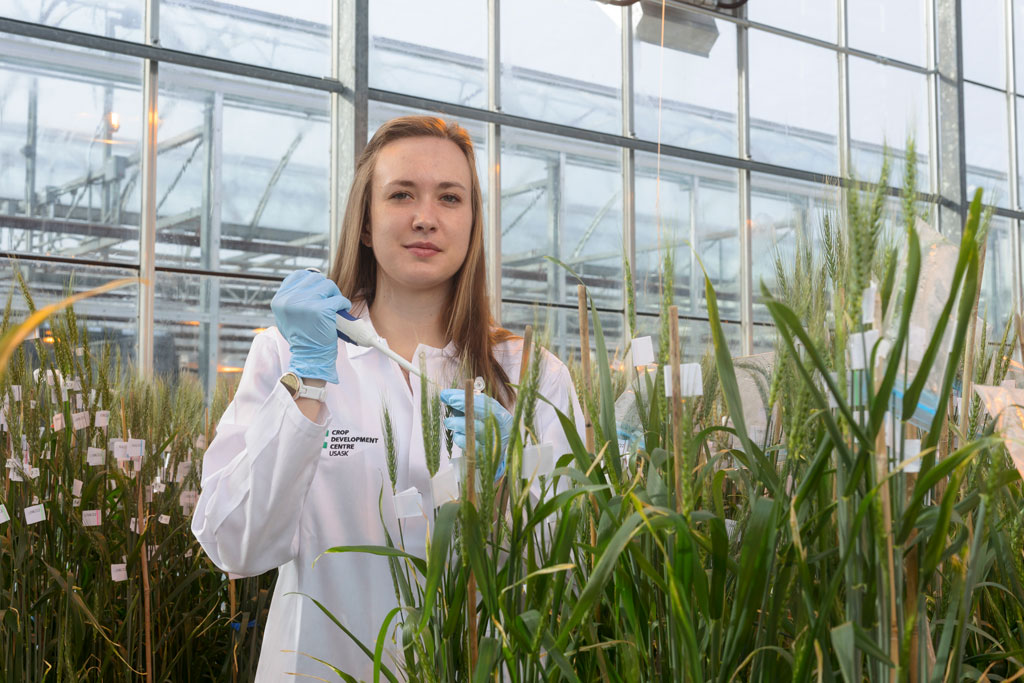

Hladun, originally from White City, SK, is a graduate student in the Crop Development Centre (CDC) in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan. Her research is focusing on assessing many mechanisms that contribute resistance Fusarium head blight (FHB) in wheat.

“I'm measuring many traits in wheat that allow the wheat plant to fight off Fusarium head blight, and it’s saving itself from being killed by this disease,” said Hladun.

Hladun’s undergraduate studies focused on studying human and animal diseases. After finishing her Bachelor of Science in cellular and molecular biology at the University of Regina, she then worked in an administrative role for Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Hladun had already spent her previous summers during her undergraduate program working for the Ministry of Agriculture, and she realized she had “fallen in love with agriculture.”

From that point, Hladun decided to research her options for a master’s degree, landing on the CDC’s website. Once she found Dr. Randy Kutcher (PhD) who specializes in disease resistance in wheat, she knew she wanted to conduct research in his lab.

Part of what Hladun said made Dr. Kutcher’s research stand out to her was that it all has practical applications for producers.

“The results can actually provide producers or other researchers’ information that they will need — which to me is just a fantastic concept. We’re actually helping people by doing this. You can see where it’s impacting the industry,” said Hladun.

By combining genetic data and statistical information, Hladun is looking to understand the genes resistant to FHB and help to improve varietal resistance through “marker-assisted selection.”

“It's tracking this genetic information throughout the crosses so that the breeder can identify what disease-resistant traits are still in the population,” said Hladun.

During her graduate research, Hladun collected all her field data and appreciated working side-by-side with the lab technicians in the CDC field lab, in the field, and at the University of Saskatchewan Department of Plant Science greenhouses.

Hladun is currently collecting the last set of data for her master’s thesis and her projected completion date is set for early 2023. After completing her research, she sees herself as an agronomist working directly with producers to support their work with “boots on the ground.”

What drives Hladun is seeing her work positively impact local producers. During a CDC Field Day last year, she recalls a moment after she wrapped up her speech on her project. After a long pause, one producer thanked her for how it strengthens their crop productions on their own farms.

“This one woman just put up her hand and said, ‘Thank you for doing the work that we can't do.’ It just clicked that not everyone can do what I'm doing,” said Hladun. “That's really rewarding.”